|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Essays-Ethics-Culture.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Home - Air Power Australia Website [Click for more ...]](APA/APA-Title-Essays-Ethics-Culture.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

![Sukhoi PAK-FA and Flanker Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/flanker.png) |

![F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/jsf.png) |

![Weapons Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/weps.png) |

![News and Media Related Material Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/media.png) |

|||||||||||||||||||

![Surface to Air Missile Systems / Integrated Air Defence Systems Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/sams-iads.png) |

![Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defence Page [Click for more ...]](APA/msls-bmd.png) |

![Air Power and National Military Strategy Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/strategy.png) |

![Military Aviation Historical Topics Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/history.png)

|

![Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Network Centric Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/isr-ncw.png) |

![Information Warfare / Operations and Electronic Warfare Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/iw.png) |

![Systems and Basic Technology Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/technology.png) |

![Related Links Index Page [Click for more ...]](APA/links.png) |

|||||||||||||||

![Homepage of Australia's First Online Journal Covering Air Power Issues (ISSN 1832-2433) [Click for more ...]](APA/apa-analyses.png) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated: Mon Jan 27 11:18:09 UTC 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Airpower and Collateral Damage:Theory, Practice and Challenges |

|||||||||||||||

|

Air Power

Australia - Australia's Independent Defence Think Tank

|

|||||||||||||||

| Air Power Australia Essay on Military Ethics and Culture ISSN 2201-9502 15th April, 2013 |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Introduction |

|||||||||||||||

|

One of the scandalous myths of modern history is that countries at war attempt to limit casualties among civilians. Although this may be true for some countries in some circumstances, the history of the past century clearly demonstrates that huge numbers of civilians were killed in war. At times, this slaughter was deliberate and a matter of government policy. The genocidal policies of Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong and Pol Pot come readily to mind. Of

civilians killed during interstate wars, one expert on war casualties

states that “technology” killed 46 million during the wars of the

twentieth century. Of these, 24 million were killed by small arms, 18

million by artillery and naval gunfire, 3 million as a result of

“demographic violence,” and a further 1 million due to air attack. He

noted that the figure of 1 million dead from air attack might be

higher, but certainly less than 2 million.1 Despite this relatively low figure for the number killed due to air attack, airpower acquired a questionable reputation that lingered for years. Often, air bombardment was associated with the city attacks of World War II — Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima. Horrible as these incidents were, the numbers dying due to air attacks were a small percentage of the total number of noncombatants killed throughout the war (around 5 percent). Moreover, since World War II the numbers killed by air strikes have declined dramatically. The conflicts of the past two decades have demonstrated a new capability to fight effectively with airpower, while at the same time limiting risk to those on the ground. This paper will focus on four areas: the theory of air warfare as it applied to collateral damage; the practice of airpower, which at first did not live up to the promises of the theorists, but whose effectiveness increased dramatically with the use of precision-guided munitions; current perceptions of airpower; and challenges ahead.

Air warfare over the past

three-plus decades has significantly lowered collateral damage. The

increasing use of precision weapons and improvements in

intelligence-gathering tools has made it easier to discriminate between

military and civilian targets and to strike only those of a military

nature. Moreover, this capability has carried with it a marked

reduction in risk to the attackers. Modern air warfare has reduced

casualties among both the attackers and the attacked, thus making it an

increasingly efficient, effective, and humane tool of US foreign

policy. Unfortunately, ground war remains extremely deadly, and the use

of weapons such as landmines and cluster munitions continues to exact a

high toll on civilians. International law, ostensibly designed to limit

the suffering of civilian noncombatants in war, has fallen short in

important areas. Deadly activities and weapons — largely policy weapons such as

sieges and economic sanctions—continue to kill civilians and cause

untold suffering. It is these horrific weapons that should now become

our focus. |

|||||||||||||||

The Theory |

|||||||||||||||

|

The Law of Armed Conflict governs whether or not a war is just as well as what actions are permissible in it. Some laws have been agreed to by international treaty, as in the Geneva Conventions of 1949. In the absence of codified law, nations turn to customary usage or the Just War Tradition that has developed over several centuries and has, seemingly, consistently stressed the immunity of noncombatants.2 The inauguration of balloon flight during the nineteenth century presented potentially new dangers to civilians, so in 1899 delegates from twenty-six nations met at The Hague to discuss limitations on the use of airships as weapons. Attendees agreed to a prohibition on the dropping of explosives from balloons to remain in effect for five years. When the stricture lapsed in 1904, an attempt was made to reinstate it, but only Britain and the US supported an extension, so the prohibition was not renewed.3 This was the only international attempt to limit airwar prior to 1914. World War I saw strategic bombing conducted by all major belligerents: given the primitive navigation and bombing equipment of the day, these attacks were highly inaccurate.4 Even so, bombing claimed only a small number of noncombatants — 1,413 dead in Britain and perhaps a few thousand more scattered throughout the rest of Europe.5 In contrast, nearly fifteen million died in the war, and this carnage had a profound impact on survivors. After the Armistice the great powers began discussing disarmament, and a Commission of Jurists met at The Hague in 1922-23 to draw up guidelines for regulating air warfare. Rules were drafted, but political and military leaders rejected their restrictive and impractical language. As a result, no country ratified the treaty.6 More talks were held at the Geneva Disarmament Conference in 1932, but these too proved fruitless.7 As war approached in 1938, the League of Nations passed a non-binding resolution prohibiting the intentional bombing of civilian populations, bombing of other than military objectives, and attacks that negligently imperiled the civilian population.8 This was a meagre effort, and in 1938 British jurist J.M. Spaight wrote: “The law of bombardment is very far from being clear . . . It is indeed in a state of baffling chaos and confusion which makes it almost impossible to say what in any situation the rule really is. . . From one point of view one might say, indeed, that there is no law at all, for air bombardment.”9 Generally, military commanders attempted to modify the rules already in existence regarding war on land and sea, but this was not a comfortable fit. An example was the legal maxim that armies could bombard a defended fortress even if it contained civilians. Examples over the previous century had included Atlanta in 1864, Paris in 1871, Alexandria in 1882, and Port Arthur in 1904. Using these precedents, airmen would later reason that when Allied bombers flew over German-occupied Europe and were shot at by thousands of antiaircraft guns and intercepted by hundreds of enemy fighters, all of Nazi-occupied Europe was, in effect, a “defended fortress.” Of greater relevance (and confusion), international law permitted navies to shell undefended fortresses and cities in order to destroy the military stores and facilities they contained — Canton in 1856, Tripoli in 1911, Beirut in 1912, and German coastal raids against England in 1914 and 1916. Because navies could not occupy a port as could an army, sailors were given wider latitude in shelling civilians. Aircraft, like ships, could not occupy a city, defended or otherwise, so perhaps the permissive rules of sea warfare were more applicable to airwar?10 Debates continued, but attempts at limitation failed because the airplane offered an escape from the hecatomb of the World War. No one wished to return to the trenches, so military and civilian leaders were reluctant to emasculate a weapon offering relief from that nightmare. The ambivalence of political and military leaders in addressing the legal issues regarding air warfare was also present among those responsible for devising a doctrine for employing the new weapon that offered both great hope and great uncertainties. Theorists and practitioners believed the airplane revolutionized warfare by allowing different strategies, doctrine, and organization. Novelists such as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells imagined aerial navies that would rain bombs, and terror, on urban populations, causing panic and pressure for peace. Some early military theorists took a similar approach. Italian General Giulio Douhet described airpower’s destructive potential, and paradoxical peaceful intent, in terms that echoed the dire predictions of the novelists: Who could keep all those lost, panic-stricken people from fleeing to the open countryside to escape this terror from the air? A complete breakdown of the social structure cannot but take place in a country subjected to this kind of merciless pounding from the air. The time would soon come when, to put an end to horror and suffering, the people themselves, driven by the instinct of self-preservation, would rise up and demand an end to the war — this before their army and navy had time to mobilize at all! 11 Air leaders in Britain and the US rejected such apocalyptic visions and instead argued that airpower would shorten wars and make them less bloody. They theorized that it was possible, in essence, to shoot the gun out of the enemy’s hand — to disarm him by disrupting his industrial war production. Both the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the US Army Air Forces (AAF) entered World War II with doctrines stressing precision bombing of enemy industrial centers. The RAF operations manual stated that the civilian populace was not, as such, a legitimate target. Area bombing was rejected: “all air bombardment aims to hit a particular target” and in every case “the bombing crew must be given an exact target and it must be impressed upon them that it is their task to hit and cause material damage to that target.”12 In August 1939, the month before Germany invaded Poland, the Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) sent a message to the head of Bomber Command stating RAF policy in clear terms: “we should not initiate air action against other than purely military objectives in the narrowest sense of the word, i.e., Navy, Army and Air Forces and establishments, and that as far as possible we should confine it to objectives on which attack will not involve loss of civil life.”13 The following year, during the campaign in France, the CAS reiterated this policy in a message to RAF commanders: the intentional bombing of civilian populations was illegal; commanders should identify objectives struck in advance; attacks must be made with “reasonable care” to avoid undue loss of civilian lives; and the provisions of international law must be observed.14 War’s realities would soon put these idealistic goals to the test. Bombing doctrine in the US was similar. Officers at the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Alabama, believed that a country’s economy was complex but fragile. Key nodes within that economy—the transportation system or specific factories that manufactured crucial industrial components—were disproportionately vital to smooth operation. If this “industrial web” were disrupted, the entire system would suffer debilitating shock waves.15 The doctrine manual that the AAF took into the war listed several potential target systems: raw materials, rail and motor transport, power plants, factories, steel mills, oil refineries, “and other similar establishments.” There was no mention of targeting population centers or popular will.16 As in Britain, the city-busting theories of Douhet were rejected for a focus on industrial infrastructure that made a nation’s war economy operate. Although humane standards were important, military efficiency also played a role. An enemy country would contain thousands of potential targets—things of value or of importance—but only a finite number of bombs, planes, and crews were available. Which targets were more vital than others? Prioritization was necessary to separate the critical from the trivial, and industrial strength seemed a logical top candidate. In addition, airpower strategists in Britain and the US believed that precision bombing of military targets would not only disrupt the war economy, but would also cause revulsion among the populace that would then clamour for peace. In other words, airwar was so potent that it would deter war, but if war nonetheless broke out, it would be over quickly, and the number of people killed would be fairly small—especially as compared to the fifteen million that had died in the Great War. Airpower would humanize war.17 Although

this notion may seem peculiar today, it is precisely such thinking that

underpins the nuclear deterrence doctrine that has been operative since

the early 1950s. Nuclear war would be so awful as to be unthinkable;

therefore, it will not occur (that is, as long as one is prepared to

wage it). It was no coincidence that the motto of Strategic Air Command

— the custodian of US nuclear-armed bombers and missiles throughout the

Cold War — was “peace is our profession.” The nuclear deterrent

posture, backed by thousands of nuclear weapons among a number of

countries, remains in place today. |

|||||||||||||||

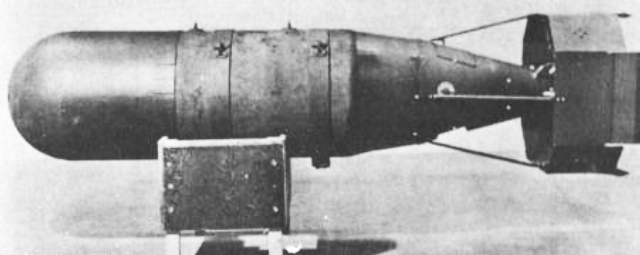

It is not widely known that guided bombs were used extensively during the latter half of World War II by Germany and the United States, but these early weapons were severely restricted in capabilities. Depicted is an AAF operated radio controlled VB-1 Azon, used in the CBI and Mediterranean theatres (U.S. Air Force image). |

|||||||||||||||

The Practice |

|||||||||||||||

|

World War II proved to be far different than predictions. Airpower did not deter armed conflict as had been hoped—although neither did land power, sea power or the policy of appeasement. Nor did airpower ensure a short war, although it did make the war shorter — especially in the Pacific. Germany had bombed urban centers in the Spanish Civil War (Guernica) and again in the opening stages of World War II (Warsaw and Rotterdam). In 1940 it was to be England’s turn. In the summer of 1940 Hitler gleefully predicted to Albert Speer: Have you ever seen a map of London? It is so densely built that one fire alone would be enough to destroy the whole city, just as it did over two hundred years ago. Göring will start fires all over London, fires everywhere, with countless incendiary bombs of an entirely new type. Thousands of fires. They will unite in one huge blaze over the whole area. Göring has the right idea: high explosives don’t work, but we can do it with incendiaries; we can destroy London completely. What will their firemen be able to do once it’s really burning?18 Hitler’s frightening vision was very near. The fall of France in June 1940 left Britain alone against Germany, and the ensuing Blitz against British cities left the country reeling. Tens of thousands of civilians died under German bombs, but surrender was unthinkable. Yet, Britain could not retaliate with its army — which had been thrown off the continent at Dunkirk — or with an overstretched navy fighting for its life against German submarines and land-based aircraft. The only hope of hitting back at Germany and eventually winning the war lay with Bomber Command, but operations quickly demonstrated that prewar doctrine had been unrealistic. British bombers were too small, too slow, too vulnerable, and too few. German fighters and antiaircraft guns decimated the attackers, so Bomber Command retreated to the safety of night, something for which it was neither trained nor equipped. (The Luftwaffe suffered the same problems when attempting to bomb Britain in daylight, so the Blitz was also carried out at night.) Worse, dismal winter weather adversely affected navigation, target acquisition, and bombing accuracy. The Butt Report of 1941 revealed that only 33 percent of bombs dropped during British night attacks fell within five miles of the intended targets; strikes on moonless nights were even more inaccurate.19 Although Britain’s intent was precision bombing, in practice, it became area bombing. Aircrew survival dictated night area attacks, and there was little alternative other than not to attack at all.20 Moral constraints bowed to military necessity, and this led air leaders down a precarious path. By early 1942 the RAF’s night offensive was targeting German cities, partly out of frustration over abysmal bombing accuracy and partly in retaliation for similar attacks on British cities by the Luftwaffe. The German raid on Coventry in November 1940 had been a turning point: Prime Minister Winston Churchill then directed the RAF to aim for city center on missions over Germany. As he put it: “Our plans are to bomb, burn, and ruthlessly destroy in every way available to us the people responsible for creating this war.”21 Air Marshal Arthur Harris, who took over Bomber Command in February 1942, agreed with the concept of area attacks dictated by his civilian superiors. Philosopher Michael Walzer has examined the moral implications of this issue.22 Early in the war British leaders argued that a combination of reprisal, revenge, and military necessity made city bombing both necessary and acceptable. Although rejecting the motivations of reprisal or revenge — in my view far too summarily — Walzer looked closely at the rationale of military necessity. Arguing that the triumph of the Nazi state was too awful to contemplate, he conceded that in the dark days of 1941, before the Soviet Union and the US entered the war, the future looked bleak for Britain. Her only hope of hurting Germany and ultimately achieving victory was through strategic bombing. Given the inaccuracy of the night strikes, it was obvious that thousands of civilians would die if such a strategy were employed. Viewing this as an instance of “supreme emergency,” Walzer concluded that such a strategy was distasteful but morally acceptable. However, he then argues that this justification evaporated when the Allies began winning the war. With the spectre of defeat no longer looming, with Allied armies closing in on the Reich, and with greatly enhanced bombing accuracy, city busting lost both its necessity and its acceptability. At least such is the position of a philosopher writing several decades after the event. At the time, ultimate victory was not so obvious, and a contemporary observer took a different view. J.M. Spaight, the British jurist who had earlier complained of the lack of legal guidelines for airwar, argued in 1944 that total war meant workers in factories and transportation systems were “warriors” not non-combatants. An attacker was therefore “fully entitled to put them out of action.” In addition, German cities were all “battle-making towns” and thus legitimate military targets.23 A more recent study echoes this view: “the cities of Europe and their inhabitants represented not merely another target among many. They stood at the epicenter of modern warfare. They were sites of production; they delivered essential economic and demographic resources to battle.” The urban populations “were more than passive victims.”24 War in practice was considerably different from war in theory, and people of intellect and integrity could disagree even on the most basic premises. US air doctrine also evolved during the war. The AAF’s losses in daylight strikes were severe, culminating in the Schweinfurt mission of October 14, 1943, when sixty B-17s and more than six hundred crewmen were lost — over 20 percent of the attacking force. Nonetheless, American air leaders clung tenaciously to their daylight precision bombing doctrine and convinced themselves that given available equipment and training, only a daylight precision campaign made sense. An invasion of France offered no hope of success before mid-1944, and something had to be done in the meantime to take the war into Germany and relieve pressure on the Soviets, who were already making noises about a separate peace — the route they had taken in 1917. Britain and the US could not allow that to happen again. The Pacific air campaign also posed problems for the AAF. Bombing accuracy was worse than in Europe because of the greater distances involved and the unexpected 200 mph jet stream at 35,000 feet where the B-29s generally flew. In addition, due to the closed nature of Japanese society, Allied intelligence concerning its economy was inadequate.25 Japanese industry was less centralized than in Europe: rather than located in large factories near towns, it consisted of numerous small shops spread throughout the cities. In order to destroy an aircraft assembly complex, one had either to identify and strike several dozen “cottage factories” or destroy a large section of the city, eliminating the dozens of small factories it contained. Area bombing could be done at night with less risk to the attackers, but it certainly crumpled the ideal of not targeting the population that had been US doctrine for two decades. But the war had to be won, and Japan was a particularly tenacious opponent: more than 20,000 Americans died at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and the Japanese defenders suffered nearly 150,000 fatalities. Moreover, on Okinawa over 160,000 civilians died—caught in the crossfire between the opposing armies.26 One can debate the numbers of projected casualties that would have resulted in the planned Allied invasions of the home islands, but such landings would likely have cost millions of American and Japanese lives. Air attacks, culminating in the two atomic strikes, seemed an expedient alternative, and no less inhumane than starvation of the civilian populace through the slowly tightening naval blockade, or the vicious and bloody land campaigns already scheduled.27 An important issue often overlooked regarding strategic bombing attacks concerned the efforts taken by defenders to thwart the bomber crews. Germany and Japan were doing everything possible to decrease the accuracy of the Allied attacks. Indeed, the RAF’s move to night operations in 1940 was a result of successful German air defenses. But at night, the Germans blacked out city lights and jammed radio navigation signals designed to help the bombers pinpoint their targets. To fool the AAF bombers in daylight, the Germans and Japanese built fake factories and camouflaged real ones, and then built smoke generators to deliberately obscure targets. They launched hundreds of interceptor planes and thousands of artillery shells to shoot the bombers down. These activities greatly distracted the bomber crews, making their aim less accurate. Consequently, the bombers often missed the intended targets and instead bombed something else, often resulting in civilian casualties.28 Who was responsible for this collateral damage — the crews that dropped the bombs or the defenders that deliberately worked to make those bombs hit something else — usually innocent people? Unquestionably, many noncombatants were killed in the Allied air attacks of World War II, but relative to the total number of deaths in the war, air attack—as had been predicted by prewar air theorists—was a surprisingly discriminate weapon. Perhaps 40 million civilians died during World War II, and of those, the US Strategic Bombing Survey states that 635,000 died in Germany and Japan due to Allied air attacks.29 The Germans and Japanese claim the number is higher. Hans Rumpf, Germany’s general inspector for fire services during the war, estimates that over 600,000 died in Germany alone. He states that a further 182,000 civilians died in other European countries as a result of air attack, including 60,000 in Britain killed by German bombs, rockets, and missiles.30 Even so, these numbers are a fraction of the total war dead. For example, over 6 million people died at the hands of the Japanese, but less than 600,000 of those died via air attack. Indeed, at Nanjing the Japanese murdered over 100,000 Chinese using small arms and swords.31 Thus, even if Gil Elliot’s maximum of two million dead due to air attack is used, it means that 95 percent of the civilian dead in World War II were claimed by genocide or traditional means of land and sea warfare—they were shot, shelled, starved to death, or succumbed to disease. The plight of civilians subjected to air attack — at least as practiced by the West — improved after 1945, although many noncombatants died in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Statistics for the Korean War are unreliable,32 but Guenter Lewy provides plausible figures for Vietnam. According to his research, around 587,000 Vietnamese civilians, both North and South, were killed in the fighting. Of those, the Viet Cong assassinated 39,000 southerners, and another 65,000 civilians died in US bombing operations over the North. The bulk of the Vietnamese non-combatant dead, 483,000, were therefore killed in the South. As to cause of death: based on those admitted to hospitals in the South between 1967 and 1970, Lewy estimates that 66.5 percent of all injuries resulted from mines, mortars, guns, and grenades. Shelling or bombing injured the other 33.5 percent. If these percentages are used for the entire war, and if we assume that the number of those injured by shelling or bombing are equal (Lewy doesn’t break this category down), and if we assume that those killed met their fates in the same percentages as did those who were wounded—and all of those are big ifs—then of the 587,000 Vietnamese civilians that Lewy states were killed during the war, around 146,000 (25 percent) died from air attacks. The other 75 percent, over 440,000 people, were killed by ground or naval action.33 Since Vietnam the number of civilian casualties has dropped dramatically in conflicts involving the US. In the 1991 Gulf War, Greenpeace estimated that 5,000 Iraqi civilians were killed by air attack, but other researchers put the figure at less than 1,000.34 Although thousands of tons of bombs were dropped on targets in Iraq during Desert Storm, damage to the civilian population was minor, which amazed Western observers. Milton Viorst wrote: “Oddly, it seemed, there was no Second World War-style urban destruction, despite the tons of explosives that had fallen. Instead, with meticulous care—one might almost call it artistry—American aircraft had taken out telecommunications facilities, transportation links, key government offices, and, most painful of all, electrical generating plants.”35 Another visitor, Erika Munk, wrote in similar terms: “We expected to find enormous unreported destruction. . . . Instead we found a city whose homes and offices were almost entirely intact, where the electricity was coming back on and the water was running. . . . I think the reason we didn’t see more destruction was that it wasn’t there.” Munk estimated that the maximum number of civilians killed during the six-week air campaign was 3,000.36 This is a sizeable figure, but not in comparison to the estimated one million plus Iraqis (most of them children) who, according to UNICEF and the World Health Organization, died as a result of UN sanctions put in place before the war but not lifted until after the Second Gulf War of 2003.37 In 1995 NATO intervened to halt the fighting in Bosnia. According to Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, perhaps twenty-five civilians died from NATO’s three-week air campaign. To stop the ethnic cleansing by the Serbs in Kosovo, in 1999 NATO launched Operation Allied Force. After a 78-day air campaign, Milosevic capitulated. Despite the duration and intensity of this air campaign, Human Rights Watch estimated that fewer than 500 civilians were killed.38 Statistics for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are inconsistent, running anywhere from 500 to 1,300 dead in Afghanistan up through 2002, and from 3,000 to 7,000 dead for the first six months of the Iraq campaign.39 Human Rights Watch states that “the ground war caused the vast majority of deaths,” noting for example that at al-Hilla ground-launched cluster bomb munitions caused 90 percent of all civilian casualties.40 Another account of civilian casualties in Iraq is provided by Iraq Body Count (IBC). This organization has determined that around 85,000 Iraqi civilians died as a result of the war up through 2008. Of these, about 9,500 were the result of air strikes—11.3 percent of the total. Significantly, not only have the numbers of civilian deaths decreased since 2005, but the percentage of deaths attributable to air attack has also decreased — to 2.6 percent. In other words, IBC calculates that over 97 percent of the 60,922 Iraqi civilians killed since 2005 have been the victims of ground warfare.41

One should also note that the Israelis have gone through a similar trend in their military operations against Hezbollah and Hamas. Prior to 2004 the ratio of non-combatants to terrorists killed was around 1:1. At that point the Israeli Air Force changed its rules of engagement, tactics, ordnance and intelligence procedures. The ratio improved to 1:12 in 2004; 1:28 in 2005 and 1:24 in 2007. Indeed, in the second half of 2007 the ratio was a remarkable 1:100—for every non-combatant who died in an air attack, 100 terrorists were killed. The Israelis note, however, that operations in the densely populated areas of southern Lebanon and Gaza, where significant Israeli ground forces were employed and which required extensive air support, once again pushed the ratio down to around 1:1.42 The low numbers of deaths due to airstrikes are remarkable, especially when compared to the alternatives of sanctions or a traditional land campaign. In the ambush and subsequent firefight between US Army soldiers and Somalis in Mogadishu in October 1993, for example, 18 Americans were killed and another 82 were wounded, but between 500 and 1,000 Somali civilians were also gunned down in that 24-hour period.43 What has caused the remarkable drop in casualties in air warfare? Largely, it is a result of the precision-guided munition (PGM). Although PGMs were used in the Vietnam War, Desert Storm was the first conflict in which they played a major role. There were various types of PGMs: electro-optical, infrared, cruise missiles using TERCOM, and laser guided. This last proved to be the most widely heralded “new” weapon of Desert Storm. Because of cockpit videos necessary to track laser bombs, the world saw memorable film clips of bombs flying down airshafts and through bunker doors. Nonetheless, of the more than 200,000 bombs dropped during Desert Storm, fewer than 17,000, or slightly more than 7 percent, were PGMs.44 In addition, only a small percentage of aircraft in the US inventory were then equipped to drop such weapons. Following Desert Storm the numbers and types of PGMs increased. Over Kosovo in 1999, PGM use increased to 35 percent, and in Afghanistan the number jumped to 56 percent. In Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) of 2003, 70 percent of all bombs dropped were PGMs, and all US strike aircraft can now deliver them.45 The types of PGMs available have also expanded and been improved to allow greater accuracy and flexibility. The GPS-aided JDAM, which can bomb through clouds or sandstorms, made its debut over Kosovo. Since then, a laser JDAM had been developed that allows precision strike against moving targets. This new dual-seeker weapon was first employed in Iraq in August 2008.46 The standard figure given for JDAM accuracy is five meters, but those employing the weapons say accuracy is far better than advertised.47 Yet, PGMs are only as good as the intelligence used to guide them. To address this issue, sensors have grown both in number and resolution capability over the past two decades. Space-based cameras and radar can produce resolutions of a few feet. Airborne sensors have similar or better performance, and spotters on the ground have sophisticated GPS range finders and laser designators to accurately locate and mark potential targets.

The impact of increased

PGM use has been profound. One PGM is equivalent to dozens if not

hundreds of unguided bombs in the effects that it achieves—neutralizing

the target. Besides lowering the risk to the attacking aircrew (fewer

aircraft/sorties are needed thus putting fewer crewmembers at risk),

PGM use dramatically reduces the amount of collateral damage. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Perceptions of Air War and the Use of Force |

|||||||||||||||

|

And yet, the negative reputation that airpower had been saddled with after World War II was difficult to shake. When many thought of strategic bombing, they thought of Dresden or Hiroshima.48 Those events were certainly horrible, but it is important to remember that far more civilians died in the siege of Leningrad—over one million—than died in all of the bombing raids on Germany and Japan combined.49 Why did airpower get such a bad press through the end of the Cold War? There are several possible explanations. First, the psychological trauma produced by aerial destruction can be profound: It can occur with little or no warning and in a greatly compressed period of time, while the effects of land and sea warfare are generally felt only over the long term. The Romans destroyed Carthage as totally as the US did Hiroshima, but it took the Roman legions several years; it took one B-29 two minutes. It was the conquest of time, not of matter, that so shocked the world. Second, airpower is violent and graphic; whereas, a blockade is seen as non-violent and bloodless. A RAND study refers to airpower, and especially any collateral damage caused by it, as being “mediagenic.” It notes that collateral damage incidents are four times more likely to be reported on television than in the print media.50 Third, some view airpower as less noble than close combat and question the “morality of distance.” A US Marine Corps general recently commented: “There comes a point when a country puts young folks at risk because it becomes important for them to defend a certain way of life. . . From a Marine point of view, we can’t lose our honor by failing to put our own skin on the line.” 51 To those of such ilk, it is only honorable to kill if there is a good chance you will be killed in return. Such thinking is, to me, astonishingly foolish. Airpower offers a far more intelligent and humane alternative. Dramatic advances in weapons technology that permitted previously impossible accuracy have been crucial to limiting collateral damage; yet, there remains a tension between risk to friendly forces and accuracy that seeks to limit collateral damage, and sometimes this issue is misunderstood. During the Kosovo air campaign of 1999, for example, allied aircraft were directed to remain above 15,000 feet to avoid enemy ground fire. Some have argued that this policy was immoral or illegal because it induced inaccurate bombing, thus increasing collateral damage and civilian casualties.52 In truth, a PGM is most accurate when dropped from medium to high altitude, because that allows time for the weapon to correct itself in flight. If dropped from a lower altitude, the weapon will have less kinetic energy and its steering fins will have less time to correct the aim: the weapon will often hit short. From the pilot’s perspective, higher altitude also allows time to identify the target at sufficient distance, “designate it” (if laser guided), and launch the weapon. In short, for PGMs against a fixed target the optimum altitude to ensure accuracy is above 15,000 feet. In contrast, to ensure accuracy the optimum drop altitude for non-guided munitions is lower than for a PGM. Even so, target acquisition by the aircrew remains a limiting factor: coming in too low at 500 knots makes it nearly impossible to acquire the target, line up, and drop the bomb accurately. As a result, the best altitude for delivering unguided weapons is around 5,000 feet. However, this places the aircraft right in the thick of fire from ground defenses. Air commanders resolved this dilemma by keeping aircraft at medium altitudes, but restricting the use of non-PGMs to areas where there was little or no chance there would be civilian casualties or collateral damage. A difficulty arises when attacking mobile targets, where the key factor becomes identification. Is the column below comprised of military or civilian vehicles; if both, which are which? At medium altitudes it is difficult to make such a distinction. On April 14, 1999, near Djakovica, Kosovo, NATO pilots attacked what intelligence sources had identified as—and which indeed appeared to be—a military column. It is now known the column also contained refugees—the Serbs illegally commingled military and civilian vehicles. As a result, several dozen civilians were killed in the airstrikes.53 Could this accident have been avoided if the aircraft had flown at a lower altitude? Perhaps. Indeed, NATO then changed the rules, allowing aircraft in certain circumstances to fly lower to ensure target identification. There is a tradeoff in such instances: if flying lower increases the risk to aircrews, at what point does the risk of misidentifying a target override the risk of losing a plane and its crew? If friendly losses meant the shattering of the Alliance, were they preferable to Milosevic continuing his atrocities unchecked? The drive to limit civilian casualties and collateral damage has generated great scrutiny among military planners. Since the air campaign in Kosovo, a special software program has been used, appropriately termed “Bugsplat,” which predicts the amount of damage that could occur for a given airstrike. Planners examine a computer-generated map of the target area that contains detail regarding the size, construction materials, and function of surrounding buildings. Planners can specify the type of bomb used, warhead size, attack path, fuze setting, and other factors for a specific target. The computer program then estimates how much damage, if any, would occur to nearby buildings if munitions hit on target, or if they missed. Based on the results, planners can then modify the size of the warhead, weapon type, attack path, and other variables to drive the anticipated damage results lower.54 In some cases, the target might be avoided altogether if “Bugsplat” indicates that significant collateral damage would occur.

Even so, mobile targets

pose special problems. Because of their nature, aircrews will have less

time to determine their identity. For example, if a vehicle suspected

of being a Scud missile launcher is seen headed for a tunnel, the pilot

must quickly decide to either hit it—and risk the chance that it is

actually a civilian fuel truck — or hold up and allow the vehicle to

escape — which could then mean that if it is a Scud, that it could

re-emerge an hour later, after the aircraft is gone, and be launched,

often against civilian targets. Accelerating the decision-making

process for hitting mobile / fleeting targets to enhance military

effectiveness, while still ensuring the protection of civilians, will

not be an easy task. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

The Challenges Ahead |

|||||||||||||||

|

Jus ad bellum and jus in bello are different but related concepts: the first refers to reasons for going to war, and the second relates to actions that occur during the war itself. Generally, a firewall separates these two concepts because military actions in war should not be judged by the validity of the reasons politicians chose to prosecute the war in the first place. Thus, a combatant may not exceed the law in order to remove a particularly nasty opponent. Significantly, this is not the case in Islamic law where a just cause allows “any means to further that cause.”55 Indeed, Osama bin Laden explicitly argues that because the United States is evil and makes war on Islamic peoples, everyone living in America is guilty of such offenses and deserves to die. There is no distinction between military and civilians to such terrorists.56 Regardless, for a variety of reasons the firewall between jus in bello and jus ad bellum is breaking down. Internationally-sanctioned interventions are more prevalent, and they are occurring under the rubric of humanitarianism. In some cases, like Kosovo and Afghanistan, the West partly justified intervention to prevent obnoxious acts committed during internal wars — setting a controversial precedent. Nonetheless, because the West justified intervention in moral terms, the use of force had to be above reproach. The world expected higher standards of conduct from the coalition forces engaged in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq than were required of those they were fighting. Part of the problem is that military planners are harnessed to an archaic Clausewitzian view of war that emphasizes the destruction of the enemy’s armed forces.57 As a consequence, targeting is viewed in legal terms as referring largely to military forces and those things directly supporting them.58 For example, if a factory is attacked because it is making military equipment, that factory is a legitimate military target. If, however, that factory makes civilian shoes but is attacked because it is owned by the enemy dictator’s brother and striking it increases pressure on the dictator to make peace, most lawyers would argue that striking the target is illegal. Such a view stems from an outdated vision of warfare. Airpower makes coercive strategies increasingly possible and successful—and “successful” means incurring less loss of life and damage to both sides. The law must catch up to airpower’s increasingly effective coercive capacity.59 Another dilemma concerns the requirement that military commanders protect the lives of their own forces and not put them at undue risk, while simultaneously limiting noncombatant casualties and collateral damage. This dilemma has been aggravated by Iraqis, al Qaeda, Serbs, and the Taliban deliberately commingling military targets with civilians. Such tactics include placing surface-to-air missile sites on or near hospitals and schools, installing a military communications center in the basement of Baghdad’s al-Rashid Hotel, or simply using civilian refugees as shields, as the Serbs did in a military encampment in the woods near Korisa, and as the “Fedayeen” did south of Baghdad in 2003.60 Such activities are illegal, but what response is appropriate? Allowing this practice to go unpunished is simply rewarding bad behavior, but is there an alternative to turning the other cheek, especially when the price for doing so could be increased military casualties? This is a contentious issue that centers on an interpretation of the rules of discrimination and proportionality. Tactically, the US generally responds by using more PGMs, more accurate PGMs, non-lethal weapons, and restrictive rules of engagement. Against Iraq, for example, coalition aircraft at times used bombs with concrete-filled warheads so as to limit collateral damage. In addition, certain military targets, like bridges, were struck only at night to minimize the possibility their destruction would injure civilians. But what if these efforts at mitigation are insufficient? Targeting lies at the heart of this issue. More precisely, some targets are considered “pre-planned” while others are not. The problem of “pop-up” or fleeting targets has already been noted: what if a target presents itself and there is little time to analyze it? More significantly, what if friendly troops being attacked by enemy ground forces? This situation, termed “troops in contact,” has proved a thorny problem. Ordinarily, pre-planned targets are thoroughly vetted in advance of an airstrike to ensure intelligence has identified the correct target and that collateral damage will be held to a minimum—the “Bugsplat” process noted above. The degree of collateral damage anticipated determines what level of authority is necessary—the air commander, theater commander, or even the president—to authorize the airstrike. In a troops-in-contact situation these safeguards are usually bypassed. Forces on the ground that are under attack often call in an airstrike to assist them. A responding aircraft will be given the location of the enemy—it may be GPS coordinates, but may simply be a general description of a building where enemy fire is originating. The pilots then do their best to identify the enemy and deploy their weapons so as to protect friendly ground forces in trouble. It is in this situation where most mistakes occur. Human Rights Watch completed a study of collateral damage incidents in Afghanistan and determined that the vast majority of cases where air-delivered weapons caused civilian casualties were troops-in-contact situations. The statistics are compelling. In the thirty-five airstrikes that caused collateral damage during 2006 and 2007, only two occurred as a result of pre-planned strikes. Thus, over 95 percent of the thirty-five airstrikes resulting in collateral damage involved troops-in-contact—those instances when the rigorous safeguards taken at the air operations center to avoid such mistakes were bypassed.61 Given that there were 5,342 airstrikes flown by coalition air forces that dropped “major munitions” during those two years, the number causing collateral damage was a mere .65 percent of that total.62 Yes, any mistake is deplorable, but that is still a remarkably small number. The problem is fundamental: there are friendly troops in contact. When our leaders put ground forces in harm’s way, it is inevitable they will be attacked by the enemy and then call for help from the air. The potential for making fatal mistakes then comes into play. It should thus not come as a surprise when the US death toll in Afghanistan began building towards a new high in 2009 that an Army spokesman stated bluntly: “It is what we expected. We anticipated that with forces going in, increased number of troops, increased engagement, you are going to have increased casualties.”63 The solution to lowering casualties, on both sides, seems apparent: avoid putting in ground forces. In September 2009 NATO aircraft struck two fuel trucks that had been hijacked by the Taliban. The strikes killed numerous civilians. Who was at fault? The crewmembers dropping the bombs, the Taliban who hijacked the trucks and then invited nearby villagers to help themselves to free gasoline, or the NATO ground troops who insisted on the airstrikes because the fuel trucks presented “an acute threat to our soldiers.”? Obviously, if friendly forces had not been present, the trucks would not have been struck and innocent lives would have been spared.64 Also illustrative of the negative impact an occupying ground force can have on a nation are the priceless ruins of ancient Babylon that have suffered so grievously at American hands. The US Army actually turned these ruins into a military base, Camp Alpha, causing “major damage” according to UNESCO. The report of the UN’s cultural agency stated that “foreign troops and contractors bulldozed hilltops and then covered them with gravel to serve as parking lots. . . They drove heavy vehicles over the fragile paving of once-sacred highways.” When fortifying this new base against indigenous Iraqis, the soldiers “built barriers and embankments . . . pulverizing ancient pottery and bricks that were engraved with cuneiform characters.” Among the structures suffering most was the famed Ishtar Gate, and the damage will be extremely difficult if not impossible to repair. 65 It is of more than passing interest that the Russian ambassador to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, views the US as repeating all the major mistakes that his own country made when Russia invaded Afghanistan nearly thirty years ago. He stated: “After we changed the regime, we should have handed over and said goodbye. But we didn’t. And the Americans haven’t either.” Kabulov is especially critical of President Obama sending in 34,000 more ground troops—the same strategy that backfired on Moscow: “The more foreign troops you have roaming the country, the more the irritative allergy toward them is going to be provoked.” The Taliban seems to agree with that assessment, as stated flatly in an interview conducted by a British reporter. The subsequent article’s title says it all: “The More Troops They Send, The More Targets We Have.”66 This is a depressing prophecy. It is alarming, but should not be surprising given the above comments, that recent polls show that Afghanis blame their country’s travails more on the US and NATO than on the Taliban: only 47 percent have a favorable opinion of the US, and 25 percent actually hold that attacks on US/NATO forces are justified.67 Such animosity appears to be mutual. A US Army report on the mental health of soldiers and marines serving in Iraq contained some remarkable findings. When asked, 62 percent of marines and 53 percent of soldiers responded that they felt non-combatants need not be treated with dignity and respect. Worse, 60 percent of all marines and 45 percent of all soldiers surveyed stated they would not report a unit member that they saw killing an innocent non-combatant. These are astounding findings, reported by the military itself, which cast an ominous cloud on ground operations.68 ♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦ Aircraft were first used in war in 1911 when Italy fought the Ottoman Empire in Libya. When an Italian aircraft bombed Turkish infantry positions the Turks claimed, falsely, that it had struck a hospital and killed several civilians.69 It would seem that the propaganda value of collateral damage caused by air attack, both real and imagined, was recognized nearly as quickly as the importance of bombing itself. It is therefore surprising that given the seriousness of collateral damage incidents, the US military has not been more proactive in investigating and then releasing findings concerning such incidents. When asked about this, one high-ranking military public affairs officer responded that such activities “were not command essential.”70 This is shortsighted. Given the military’s access to numerous sensors, videos, pilot reports and those from personnel on the ground, it is probable that no one is better able to determine the facts in such cases.71 If the military abdicates this responsibility, someone else—with far fewer facts available to them—will fill the information vacuum. The resulting reports, probably inaccurate and fragmentary, will be accepted as true in the absence of authoritative evidence. The Israelis are also familiar with this problem of illegal commingling and propaganda; as a result, they have formed special teams that accompany all ground units into action and the mission of these new units is to conduct “operational verification.” Armed with video cameras and tape recorders, they “document the story in real time” to counteract the tales spread by the terrorists.72 The

“War on Terror” highlights many of the challenges noted above.

Terrorists often use illegal methods and weapons to achieve their

goals; yet, they are in some ways shielded from the consequences of

these illegal acts. Terrorists often operate in urban areas,

deliberately commingling with civilians and occupying protected

structures such as mosques and schools. They are well aware that they

can usually get away with such practices because the US and other

Western countries will be loath to strike—which they are legally

entitled to do—for fear of causing collateral damage and incurring

international censure. Terrorists are often organized in small, highly

mobile and separated units, thus easily blending into the civilian

populace (their intent) and making it extremely difficult to track

them, much less strike them.73 These are all formidable challenges

for any type of military force to address, including airpower. |

|||||||||||||||

Conclusion |

|||||||||||||||

|

We must confront what one could cynically call “the myth of noncombatant immunity.” The attempts to reduce the suffering of noncombatants during war, although noble in intent, only paste a fig leaf on the problem. In reality, civilians have always suffered the most in war. This was never truer than in the twentieth century, when estimates of those who died in war range as high as 175 million, the majority of whom were noncombatants. Worse, the number of civilians dying in war as a percentage of total deaths has increased dramatically over the past century. These statistics indicate that the principle of noncombatant immunity is at best a goal we have tried unsuccessfully to achieve, but at worst is a myth that hides the truth. Innocent people have always suffered the most in war, especially in the traditional forms of land and sea warfare. Throughout the past century, indiscriminate killers included unrestricted submarine warfare, landmines, blockades, sanctions, sieges, artillery barrages, starvation, and genocide — as well as some bombing operations in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.74 Centuries of evidence show that blockades, sanctions, and sieges have a percolating effect: they start killing at the bottom levels of society and slowly work their way upwards. Over one million civilians died at Leningrad during World War II, while more than 20,000 civilians died at Sarajevo in 1993; yet, sieges are still legal under international law.75 Regarding blockades, the more than 800,000 German civilians who died as a result of the Allied starvation blockade in World War I were not soldiers, politicians, or even factory workers.76 Instead, the first to die were the old, the young, and the sick. Eventually, and only very slowly, did the effects reach the upper levels of society. Such odious results also were the norm in Iraq during the 1990s as a result of sanctions imposed by the UN to pressure Saddam Hussein, sanctions that killed over one million civilians; it was not Saddam Hussein and his generals who went to bed without their supper. The sanctions imposed on Haiti between 1991 and 1993 in an attempt to push out the military junta in power were similarly egregious. During those two years the Haitian economy was devastated: unemployment soared to 70 percent, inflation doubled, GDP dropped 15 percent, and 1,000 children died each month as a direct result of the legally levied sanctions.77 Small wonder that two observers wrote a critical and cynical article on the matter titled “Sanctions of Mass Destruction.”78 Some have argued that such suffering is the fault of the country’s leaders who refuse to give in, or who hoard food and medicine for themselves—and not the responsibility of those who impose these deadly sanctions. History shows, however, that countries usually react to attacks in war by accepting casualties to achieve their objectives, and they will protect whatever allows them to continue the fight. They will sacrifice the weakest segments of society so that the strong can fight on. Nations at war for their survival (or the survival of their leaders) cannot afford to take a “women and children to the lifeboats first” stance. Thus, dozens of cases over several centuries demonstrate what should have been anticipated after the US and UN leaders imposed sanctions on Iraq and Haiti. It is disingenuous to claim afterwards that they didn’t know the gun was loaded. In truth, blockades and sanctions are deliberately genocidal policies that must be outlawed. It is time to return to the basics. If the intent of international law is to limit civilian deaths in war, then we should look at the past century to see what methods of war and which weapons have been most destructive, and move for legislation to limit them. The arithmetic is clear. The biggest killers have been blockades, sanctions, sieges, landmines, artillery, small arms, genocide, starvation, and despotic rulers who murdered their own people in order to consolidate power. These are the areas that the law should examine, rather than concern itself with putting further restrictions on airpower, which has proven to be, as Marc Garlasco from Human Rights Watch has stated, “probably the most discriminate weapon that exists.”79 To continue to put additional restrictions on what targets can be attacked from the air, with what weapons, and in what manner, makes little sense. It may reduce the number of civilians killed in war by a hundred people here or there, but it will ignore the hundreds of thousands who die in traditional forms of war. Focusing on airpower, as if it were the real problem, is akin to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

It must be our goal and

the main focus of the law to employ weapons and strategies that limit

collateral damage and civilian casualties. Clearly, the events of the

past two decades have revealed the stark contrast between the

discriminate and precise nature of air warfare — especially as

conducted by the US and its allies — and that of land warfare. But even

more to the point, the appalling slaughter of one million Iraqi

civilians as the consequence of UN-imposed sanctions must become the

primary focus of the legal community. There is a gaping hole here that

must be filled; yet it is barely even acknowledged. War is indeed hell.

People suffer in war, innocent people, and this is precisely why

countries try to avoid war, and why they decide to end it. The

challenge is to fight only when it is necessary and then to exercise

forbearance in war, while also achieving the stated political

objectives. Airpower now offers the greatest possibility of achieving

these diverse goals, which means international law must turn its focus

to the far more prevalent and deadly threats. |

|||||||||||||||

Endnotes/References |

|||||||||||||||

|